Trending

AA

+Text Size

- Small

- Medium

- Large

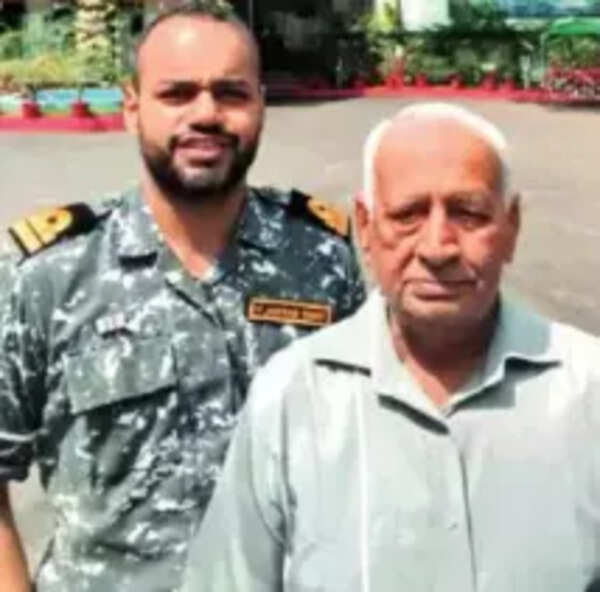

Newlyweds Lt Vinay Narwal and Himanshi’s joy turned to tragedy six days after their Mussoorie wedding when Narwal was killed in a terrorist attack in Pahalgam, Kashmir. The couple had chosen Kashmir over Europe for their honeymoon due to visa delays. Narwal’s body was returned to Karnal, draped in the Tricolour, amidst widespread grief and calls for retribution.

KARNAL/GURGAON: Amid dancing, feasting and photoshoots, Karnal boy Lt Vinay Narwal and Gurgaon girl Himanshi got married in Mussoorie on April 16. Six days later, a picture of a dazed Himanshi slumped next to her husband’s body on a verdant meadow lined with pine trees in Pahalgam became the image of terrorism’s devastating fallout.

And while the image cannoned around news and social media on April 22 afternoon after terrorists gunned down 26 tourists, among them the 26-year-old Navyman, the sound of celebrations from the couple’s destination wedding still echoed in Karnal as Narwal’s mother visited neighbours to distribute sweets.

The family came to know only in the evening, and a crushing sorrow drowned everything out. “Everyone in the Narwal household was so happy after the wedding,” Naresh Bansal, a neighbour who was in tears, told TOI on Wednesday. “They were even planning a ‘Mata ka Jagran’ next month,” he added.

Also read: Pahalgam Attack

Narwal and Himanshi were not even supposed to be there. The duo had a European honeymoon in mind, in the Swiss Alps, but decided on Kashmir when the visas did not come through on time.

“I was eating bhel puri with my husband when a man suddenly came and said he’s not Muslim… then shot him,” a stunned Himanshi is heard saying in one of the many videos from the attack site, which is en route to a place locally known as ‘mini-Switzerland’, circulating online.

Married In Mussoorie, Became Face Of Devastation In Kashmir Six Days Later

In a casket draped in the Tricolour, the body of Narwal – who would have turned 27 on May 1 – was flown to Delhi and then taken by road to Karnal on Wednesday. His parents and younger sister had flown to Srinagar to bring his body back.

According to initial reports, Narwal was shot in the chest, neck and left arm.

“I pray that his soul is in peace, and he has the best time wherever he is… we should all be proud of him in every way,” were all the words Himanshi could muster as she embraced the coffin and cried before it was taken for the last rites, accompanied by slogans of “Hindustan zindabad, Pakistan murdabad” from the large crowd that had turned up to express condolences.

Narwal and Himanshi, a PhD scholar who teaches in Gurgaon, got engaged two months ago after their families fixed the match. Himanshi’s father Sunil Kumar is an excise and taxation officer. Narwal’s father Rajesh is a superintendent in the GST department.

An engineering graduate, Narwal wanted to join the armed forces since school but couldn’t crack the combined defence services (CDS) exam back then. After getting his bachelor’s degree from a Sonipat college, he prepared for SSB (service selection board) and was chosen to join the Navy three years ago.

Posted at the Southern Naval Command in Kochi, he took leave from March 28 for the wedding, his family members at their Sector 7 house in Karnal city said. The wedding celebrations began with a ring ceremony on April 4, culminating in the Mussoorie wedding.

The couple left for J&K on April 21 two days after the reception in Karnal on April 19, catching a flight from Delhi’s IGI after a lunch stopover at Himanshi’s house in Gurgaon’s Sector 47. After Pahalgam, the newlyweds had planned to go to Vaishno Devi temple in Jammu. They were supposed to return to Karnal by May 1. “We had planned a big party on his return from the honeymoon,” said Amit, a relative. On May 3, the couple was to leave for Kochi, where they had booked a resthouse.

Narwal’s grandfather Hawa Singh, who retired from Haryana Police, said on Wednesday the Prime Minister should teach terrorists a lesson. “Had the attackers not been carrying guns, my grandson would have taken on at least 3-4 of them,” he said. Raghbir Singh, Narwal’s granduncle, said the family was informed by the SHO of Madhuban police station and by the SP office Karnal. Bhusali, the village the family is from, was in deep shock. Many had celebrated Narwal’s wedding at a resort on Kunjpura road in Karnal.

The Indian Navy, in a post on its official X account, said on Wednesday that the force and naval chief Admiral Dinesh K Tripathi were “shocked” and “saddened by the tragic loss of Lt Vinay Narwal who fell to the dastardly terror attack in Pahalgam”. “We extend our heartfelt condolences to his family during this moment of unimaginable grief,” the post read.

Himanshi’s family is originally from Jhajjar but settled in Gurgaon two decades ago. Himanshi is the elder of two siblings. Her younger brother is in college. Narwal’s sister Srishti is preparing for the civil services in Delhi. Vikrant, a neighbour, said Himanshi’s father was very social and an active resident of the sector. “He takes initiatives for cleanliness and plants trees across the sector,” said Vikrant, adding the neighbourhood shared the family’s grief.

Haryana CM Nayab Singh Saini, who was in Gurgaon on Wednesday, called the terrorist attack on tourists cowardly. “My condolences are with the bereaved families in this time of sorrow. Govt stands fully with the families who are grieving,” said the CM. Saini spoke to Hawa Singh through a video call and assured the family that those responsible will be punished. In the evening, he visited the family in Karnal. “Today, I have lost my grandson, tomorrow it can be someone else,” Singh told the CM.

Narwal’s uncle Surjeet Narwal said, “I request PM Modi to shut petty missions, find those terrorists, kill each one of them in the same manner they killed our people. The PM should find them and destroy them.” Calling Narwal a true gentleman, he said the officer would always touch his feet when he met him. “We celebrated his wedding merely a week ago and now we are forced to make arrangements for his funeral,” he said.

Vinay’s colleagues remembered him as a cheerful officer. “He was deeply committed to his duties,” a Navy officer said.

End of Article

Follow Us On Social Media

Previous

Only 4 countries begin with ‘R’— Can you name them all?

8 strangest-looking animals and places to spot them

10 things to know before getting a Labrador as a pet dog

10 beautiful yellow birds that will brighten your day

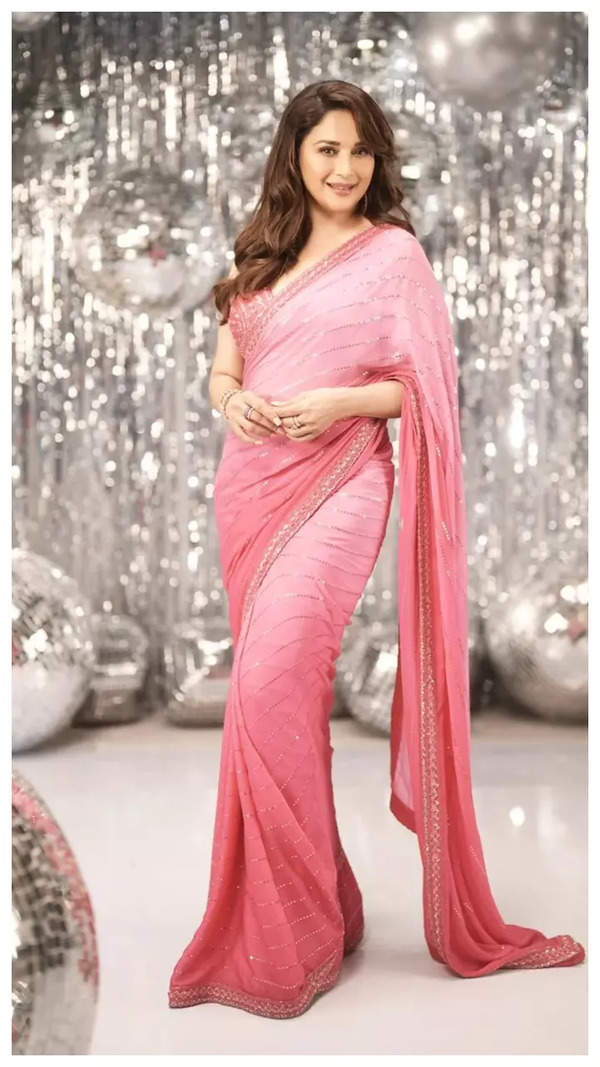

Madhuri Dixit Nene’s best saree looks

10 gentle ways to discipline a child

Gulki Joshi’s Ethnic Elegance: Stunning Sarees and Chic Suits

Sushmita Sen shines bright with her naturally glowing beauty

Weight Loss Diet: How to make high-protein Chana Dal and Paneer Cheela for breakfast

Next

- 1

- 2

- 3

Why your recorded voice sounds like a stranger

Bollywood celebs who run businesses like a boss

6 Reasons to drink lemon ash gourd juice in the morning

How to spot a toxic co-worker, as per psychology

Katrina Kaif to Alia Bhatt: 5 times Bollywood divas stole the spotlight as bridesmaids

6 things that parents of confident and mentally strong kids refuse to do

How sleeping position affects your spine: Are you damaging your back every night?

How Diljit Dosanjh transformed Punjabi pop culture with music, movies and magnetic charm

- 1

- 2

- 3

Way to Improve Communication Skills

Unique Mixing Recipe in Schedule 1

Tired of too many ads?go ad free now

In City

Entire Website

- ‘It was a distressing scene, injured children, women were crying’: Terrorists storm shop, family narrowly escapes Pahalgam terror attack

- ‘He never missed wedding or Sunday coffee’: Pune’s Santosh Jagdale, victim of Pahalgam terror attack, remembered as tireless traveller and devoted family man

- 170 from Karnataka still in Jammu & Kashmir; families recall close call with terrorists

- For Pune’s Kaustubh Gunbote, Pahalgam trip was supposed to be much-needed holiday before big ceremony for grandchild

- ‘One terror act has killed our season’: Kashmir’s hospitality sector finds itself in a sudden freeze

- Pahalgam attack: Bengaluru techie identified himself as Muslim, told to recite from Quran and strip before being shot

- Pahalgam terror attack: Faces of a tragedy that shook India

- ‘We were eating bhel puri when they suddenly emerged, said he’s not Muslim’: Wife recalls moment Lt Vinay Narwal was shot in Pahalgam

- Pahalgam terror attack: Govt asks airlines to ensure no surge in Srinagar airfares

- Andhra Pradesh IPS officer who was CM Jagan Mohan Reddy’s intel chief arrested in Mumbai actor ‘abuse’ case

- From FBI sessions to NHL games: Director Kash Patel’s frequent use of government jets has tongues wagging about personal travel decisions

- “Josh is gonna be sick”: Hailee Steinfeld’s “Sinners” romance with Michael B. Jordan has fans teasing Josh Allen

- Derrick Henry breaks his silence and shares an update about his life as his future with the Baltimore Ravens remains unsettled

- Pahalgam terror attack: What is Indus Water Treaty and how will its suspension impact Pakistan?

- Boston Celtics vs Orlando Magic final injury report (April 24, 2025): Is Jayson Tatum playing tonight?

- Did Travis Kelce force Taylor Swift to skip Coachella and other major award shows because he’s ashamed of the Super Bowl loss?

- All 133 international students, including many Indians, who filed a lawsuit get their SEVIS records restored

- Why won’t JD Vance attend Pope Francis’s funeral? Here’s what he said

- It’s a girl thing: Trevor Lawrence’s better-half, Marissa gets her expensive diamond ring fixed after pregnancy, shares motherhood journey

- Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg, JP Morgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon and other billionaires sold billions in stock before Trump’s Tariff announcement

Tired of too many ads?go ad free now