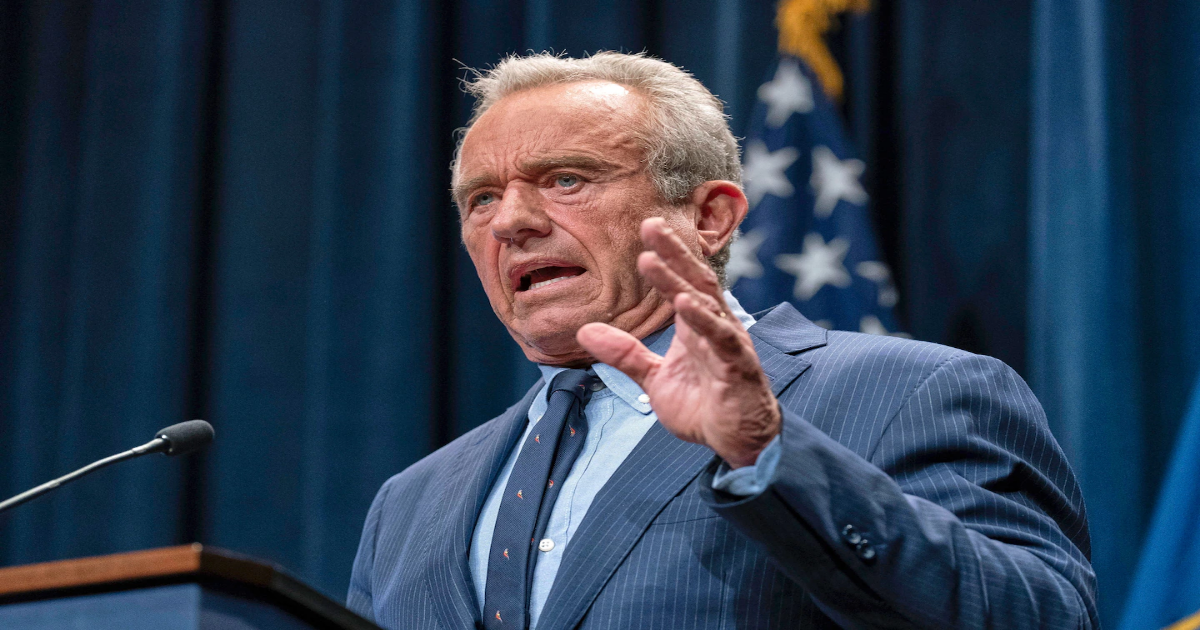

Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has called autism an “epidemic” and vowed to find the “environmental toxin” responsible. He also called autism a “preventable disease.”

These words pierced right through me and other autistic individuals whom I know. The highest-ranking health official in the country said that what I have is a “disease” and that I need to be cured. This view should be thrown in the dustbin of bad science — not legitimized.

When autistic people such as me are told we have a “disease,” it’s hard to see that as anything but demoralizing and hurtful. Do people think we should be isolated, like autistic people have been for decades? Do they think we’re at risk of spreading it? These are questions that Kennedy does not answer.

Kennedy’s reasoning for why there’s an “epidemic” is that the number of autism diagnoses has increased over the years. But as a recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report stated, the increase may be attributed to “availability of services for early detection and evaluation and diagnostic practices.” Rigorous research supports this view.

Kennedy’s rhetoric about autism suggests to me that he has met few, if any, autistic individuals. Many pay taxes, hold jobs and live ambitious lives.

David Geier, whom Kennedy tasked with leading this investigation into autism, was charged by the Maryland Board of Physicians with improper medicine practice. He has historically promoted anti-vaccine views. This should be enough evidence to show that Kennedy is not launching a good-faith investigation.

The writer is founder and president of the nonprofit Mentoring Autistic Minds.

Don’t cut autism funding

On the eve of Autism Awareness Month (also called Autism Acceptance Month), the Trump administration announced drastic cuts to federal agencies that directly support the health and well-being of people with autism and related disabilities. These cuts are not just numbers on a budget sheet; they are potentially life-altering decisions that could leave millions of Americans without the support they need.

The Department of Health and Human Services is dismantling programs and agencies, such as the Administration for Community Living, designed to help people with disabilities live independently. Helping people with disabilities remain in their homes and communities isn’t just the right thing to do; it’s fiscally responsible. Community-based support costs far less than institutional care and leads to better, less expensive health outcomes. Eliminating this agency is both cruel and shortsighted.

At the same time, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has terminated its Disability and Health Promotion Branch and laid off scientists researching developmental disabilities in children. This information is critical for understanding who needs care, where services are lacking and how disparities affect access to diagnosis and treatment. With baffling timing, HHS released the most recent report on autism prevalence (now 1 in 31 children) after slashing the office responsible for collecting the data.

Yet, even as funding disappears, rhetoric ramps up. HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., now leading the administration’s “Make America Healthy Again” commission, said that most autistic children “will never pay taxes” or “play a baseball game” or be productive members of society. These statements dangerously stereotype an entire population.

When the administration silences data collection, eliminates community-based support programs and withdraws funding from initiatives that empower autistic people, it sends a clear message that autistic lives are less valuable. Federal spending cuts and workforce reductions might be all about saving money to some, but to others it signals abandonment.

Congress can and must restore funding for disability services, research and data collection. And in that process, we must center the perspectives of autistic people.

Autistic people are not a burden to be managed. They are community members to be heard, respected and empowered.

Hoangmai Pham, Washington

Gyasi Burks-Abbott, Boston

Hoangmai Pham is founder and leader of the nonprofit Institute for Exceptional Care. Gyasi Burks-Abbott is a disability advocate and faculty member at UMass Boston.

After a diagnosis

As Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s comments about autism spark national headlines, I feel torn. Though I’m glad the topic is finally being widely discussed, the conversation still misses what families such as mine face every single day.

I’m a mom of a child with autism. I’m not writing from a lab or a campaign stage or an expert panel. I’m writing from a small home in New Mexico after late-night individualized education program meetings and therapy appointments. I’ve done everything I can think of to advocate for my son, reading through the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, combing through our school district’s budget, submitting public records requests and reaching out to principals, superintendents and state officials.

Still, nothing seems to change. Teachers with the right training are leaving, substitutes with no experience are filling in and funds that could make a real difference aren’t being used to address the daily issues Americans face.

Yes, autism diagnoses are rising. We’ve known this. What we’re not talking about nearly enough is what happens next — the waiting lists, the teacher shortages, the classrooms with no aides, no training, no space for neurodivergent kids to belong.

My son, like so many others, cannot wait for studies to be published or for the perfect hire to be made. While policies move slowly, children are struggling in real time.

We need national attention not just on what autism is, but also on how our schools, our communities and our country are responding. Right now, we are failing them.

Let this moment be more than a headline. Let it be a call to action — not through fear and blame, but through responsibility, compassion and commitment.

Eva De Luna, Sunland Park, New Mexico

She opened my eyes

One of my granddaughters is on the autism spectrum. Now a junior in high school, she runs cross-country and finishes every race; sings in the high school choir; achieved special education honor society for three years; and has been selected as the school’s student of the month.

She doesn’t read well. She has difficulty with math and sometimes gets confused. She needs help with these things. She probably won’t be able to drive — her parents are wrestling with that decision now — but she is proceeding ahead with driver’s ed anyway. Her parents are also wrestling with dating.

Regardless of the problems she faces, she is an inspiration to everyone around her, especially to her grandfather. She is the sweetest person in the world. She is able to engage with anyone, making them smile and laugh. Her parents have done a marvelous job throughout her journey — which has been similar to the one Trey Johnson described in his April 20 op-ed, “Listen to RFK Jr. on autism. Then meet my son.”

Sweet Helen is many things, but she is certainly not a burden to society, as Robert F. Kennedy Jr. described. Most important, she has opened my eyes to the need for humility and compassion for others.

In this era of reducing the federal budget, we need to discuss how we care for people with disabilities. Surely we can do both. As Thomas Jefferson wrote: “The measure of society is how it treats the weakest members.”

Hope RFK Jr. likes coffee

On Easter Sunday morning, I read Trey Johnson’s powerful April 20 op-ed about his 11-year-old son and Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s recent ill-informed comments about autism. After Mass at Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Georgetown, we wandered into Bitty & Beau’s Coffee on M Street, a coffee shop founded in 2016 with the specific mission of employing people with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

I invite Kennedy — and all Washingtonians — to visit Bitty & Beau’s the next time he’s in Georgetown. Ask for my new friends, Irene and Madison. It’ll be the best coffee of your life.

Charlie Baisley, Alexandria

An autism success story

Our son Phil was a fussy baby who did not sleep through the night or speak in sentences until age 5. He avoided eye contact and followed rigid routines. We agonized over possible causes of our son’s challenges, worrying we had done something wrong. As we followed the research and puzzled over unfounded “cures,” we realized the causes are complex, most likely occurring before he was born.

Through our efforts, the support of dedicated teachers and therapists, and Phil’s own determination, he has been a fully employed, taxpaying citizen since the 1990s, when he began working in the Clinton White House providing office support. He has earned employee awards and never misses a day, except when he and his wife are on vacation traveling the world. Phil dated, fell in love and has been married for 20 years. His siblings (who received the same vaccines he did) view him as a role model; his brother toasted him at his wedding and his sister wrote about him for her college admission essay.

In addition to his work, Phil maintains a rigorous exercise schedule. He volunteers as an advocate for people with disabilities, serving in leadership roles in advocacy organizations and on the board of his synagogue. Phil’s wife recently reminded us of a saying in the advocacy community: “If you’ve known one person with autism, you’ve known one person with autism.”

Alison and Richard Weintraub, Friendship Heights

Alison Weintraub is a retired special educator and child psychologist. Richard Weintraub is a writer and former Post employee.