George Foreman, one of the greatest heavyweights in the history of boxing, died on Friday at the age of 76.

He had 81 fights as a professional, winning 76 of them — 68 by knockout. His story is the stuff of legend: a high-school dropout who grew up poor in a tough and segregated neighbourhood in Houston, he turned to robbing people in the streets in his mid-teens before finding boxing, then a year later became an Olympic gold medalist, winning the heavyweight title at the Mexico Games in 1968.

He turned professional the following year and embarked upon a career that spanned 28 years and saw him become a two-time heavyweight world champion; the second time at the age of 45. Foreman’s record is littered with the names of heavyweight legends: Ken Norton, Joe Frazier, Muhammad Ali. He even faced a 28-year-old Evander Holyfield in 1991, such was his incredible longevity.

Here are five of the greatest moments from his career…

Olympic gold, Mexico City, October 1968

Foreman had won his first amateur fight some 21 months before the Games, in January 1967, and by the time the Olympics came around he had an amateur record of 16 wins and four defeats.

By international standards, the American was a 19-year-old novice and many wondered whether he would be overwhelmed among the world’s elite amateurs. But by the time he reached the final, having recorded decisive stoppage victories in his quarter-final and semi-final bouts, few were still wondering. Foreman’s shots were thunderously heavy and they left their mark.

In the final, Foreman faced experienced Soviet fighter Jonas Cepulis, 10 years his senior and with over 220 fights on his 12-year amateur record. It mattered not. Cepulis’ attempts to jab and move were thwarted by Foreman’s own jab, which was faster and landed with more force. Two minutes into the first round, Cepulis’ face was a bloody mess, his mouth and nose having felt the power of Foreman’s jab.

“The left jab was my number one punch,” Foreman later told BBC Sport. “I still think it was the best punch in boxing.”

Things did not improve for Cepulis in the second round. He was given a standing count midway through the round and, after soaking up more and more destructive shots from Foreman, was finally given a reprieve when the referee stopped the fight.

There were no exuberant celebrations from Foreman.

Just two years earlier, he’d been the kid hiding from the police — a mugger and a thief. “The police were chasing me down,” he told the BBC. “I climbed from underneath that house, in mud and slop, and said to myself, ‘I’m going to do something in my life; I’m not a thief’.”

What he did do was grab a small U.S. flag and hold it up high as he walked around the ring, taking a bow in front of the judges. Coming just 10 days after his compatriots, sprinters John Carlos and Tommie Smith, stood on the podium inside the Olympic Stadium and raised their fists in defiance to protest for black civil rights in the States, Foreman received a lot of criticism from those who argued it undermined the powerful protest of Smith and Carlos.

Foreman has always defended his actions, saying he “just wanted to let the world know I’m from America because I had forgotten that people can look at you and see any differences. I was just a young man so happy and telling the world my address.

“I had a lot of flak. In those days, nobody was applauded for being patriotic. The whole world was protesting something. But if I had to do it all again, I’d have waved two flags.”

In just two years, Foreman had gone from a life of petty crime to standing atop an Olympic podium, his life forever altered.

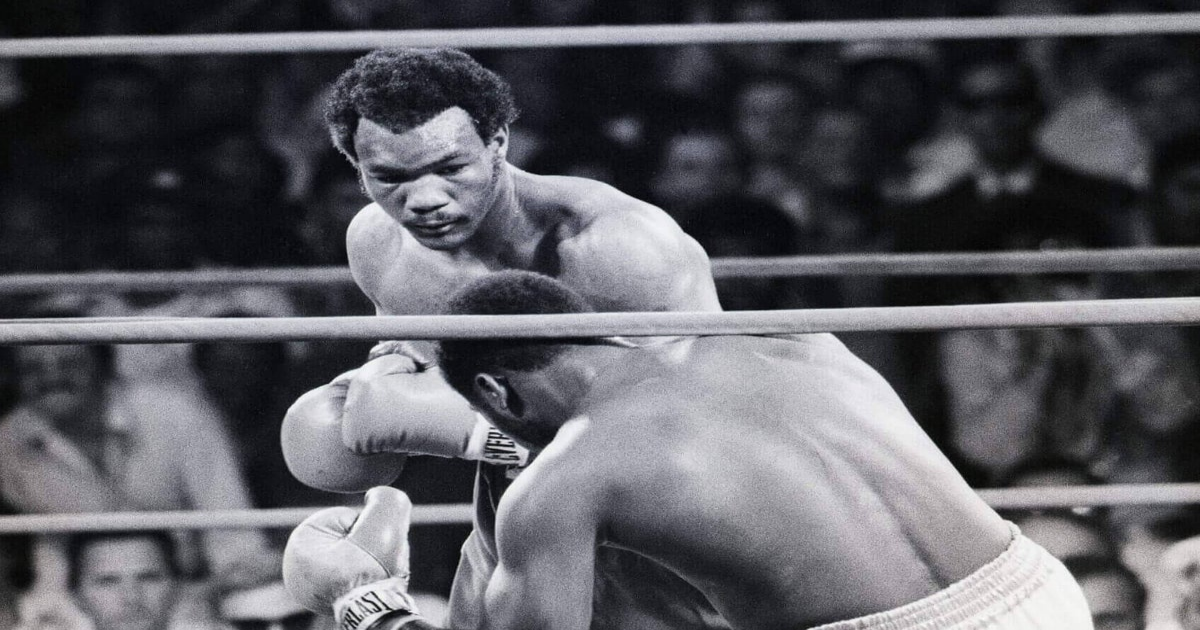

Joe Frazier vs George Foreman, Jamaica, January 1973

By the time he met Frazier for the first time in Kingston, Jamaica, Foreman had built an impressive record of 37 victories and no defeats in just four years as a professional and was ranked number one by the WBA and WBC. Frazier was the undisputed heavyweight champion and also unbeaten, with a record of 29-0, including a unanimous decision victory over Ali in 1971 in “The Fight of the Century”.

“We’ll find out tonight just how good Foreman is in punching and in taking a punch,” said the commentator Howard Cosell as the first round commenced, with Frazier the man widely fancied to win.

Not long afterwards came one of the most iconic calls in sports history: “Down goes Frazier! Down goes Frazier! Down goes Frazier!” as the heavyweight champ hit the canvas. Frazier was back on his feet swiftly but was down twice more before the end of the round, the bell offering him a brief reprieve from Foreman’s relentless power.

The second round brought three more knockdowns for Frazier. Amid the chaos, Ali’s trainer, Angelo Dundee, who was ringside to watch the fight, could be heard pleading for it to be stopped and shortly after the sixth knockdown, referee Arthur Mercante Sr waved it off. At 24, Foreman had become the third-youngest man to be heavyweight champion of the world, after Floyd Patterson and Ali.

Foreman was carried out of the ring and through the crowd of 40,000 by his team and would later say that his first victory over Frazier (Foreman beat him again three years later, in June 1976) was the “happiest time of my life in boxing because I worked so hard to fulfil my dream and become heavyweight champion. It was the first and last moment I felt that.”

George Foreman vs Muhammad Ali, Zaire, October 1974

It feels odd to include a defeat in Foreman’s greatest moments, but it would feel odder still to leave it out given the place this fight holds in boxing history and the significant impact it had on Foreman’s future.

The Rumble in the Jungle pitted a 32-year-old Ali, still on the comeback trail after his three-and-a-half-year suspension from the sport for refusing to be drafted into the U.S. army during the Vietnam War (on religious and moral grounds), against a 25-year-old Foreman, now 40-0 and fresh from a two-round destruction of Ken Norton, who was then the only man other than Frazier to have beaten Ali (though Ali gained his revenge over Norton just a few months later and would beat him again in their third fight in 1976).

The build-up to the fight was filled with intrigue and stories (Norman Mailer’s book The Fight famously took readers to the very heart of it). Both fighters spent the months leading up to it preparing in Zaire — a stay that became longer than planned when the original date of September 25 was scuppered after Foreman suffered a cut in training eight days before the fight was due to take place. By the end of October, when the fight was rescheduled for, the rainy season was fast approaching and the heat was increasingly oppressive.

Foreman was the bookies’ favourite to win and firmly believed he would fulfil that destiny. “To me, it was like a charity fight,” he told the BBC in 2014. “I’d heard Ali was desperately broke, so I thought I’d do him a favour. I got $5million and I was willing to let him have $5million.” But in Kinshasa, Ali was the clear favourite among the locals. Chants of “Ali Boma Ye!” (“Ali, kill him!”) accompanied the former heavyweight champ wherever he went and it was graffitied on buildings around the city.

On fight day, the mood was dark in Ali’s camp. In The Fight, Mailer describes how “the ring’s ropes had stretched in the heat and the sponge mat had softened. Angelo Dundee, Ali’s trainer, worried that this would make it harder for Ali to move around. There was concern over whether Foreman could seriously injure, if not kill, Ali.”

It was 4am by the time the fighters entered the ring (the fight was scheduled for prime time in the U.S.), watched by an estimated 60,000 inside the stadium and as many as one billion television viewers around the world. They were engrossed as the fight unfolded, Ali starting on the front foot before retreating to the ropes and giving Foreman the opportunity to unload while he blocked almost everything coming his way. Ali tied Foreman up whenever he could and chose his moments to counterpunch.

In the third round, Foreman landed what he felt was the biggest shot of the fight, sinking it deep into Ali’s side. As Ali fell into him, the challenger growled, “That all you got, George?”

“That scared me,” Foreman later told the BBC. “I knew there was going to be trouble then.”

After the fourth round, Foreman’s energy was spent: “It was like I’d stepped into a bucket of concrete. I didn’t know what I was doing out there,” he recalled. Foreman’s punches lost more and more of their power and by the eighth round, they seemed to carry hardly any weight at all.

Ali had looked fatigued, too, until, with 20 seconds of the round remaining, he pounced, unleashing a series of right hooks and the final left hook-right hand combination that sent Foreman crashing to the canvas. He rose slowly to one knee, but before he found his feet the fight was over, leaving Ali as heavyweight champion once again and stripping Foreman of the titles he’d held for almost two years.

It was a devastating loss for Foreman, one that his younger brother Roy said took him eight to 10 years to get over.

But it was also a loss that set him on a completely different path. One that helped cement his legacy in the sport. Without the Ali fight on his record, Foreman would still have been a great champion, but with it, he’s part of one of the most historic moments in the sport; a moment that transcends boxing.

George Foreman vs Ron Lyle, Las Vegas, January 1976

Foreman had not fought professionally since his defeat to Ali when he stepped into the ring to face Lyle, who was ranked fifth in the world at the time and learned to box during a seven-and-a-half-year stint in prison. Lyle had fought Ali the previous year, losing in an 11th-round stoppage. He was tough and expected to test whether Foreman’s mind (and body) had recovered from the loss to Ali.

A year before the Lyle fight, Foreman took part in a bizarre event called Foreman vs Five in Toronto, where he took on five professional boxers in a single night in bouts contested over three three-minute rounds (the Ontario Boxing Commission stipulated that they had to be classed as exhibitions and so no scores were announced).

Ali surprised Foreman at the event by showing up at ringside to commentate and shouting, “Get on the ropes — he’ll get tired.” The night descended into something of a circus and though Foreman later told Boxing News it was a “satisfactory night” for him, it did not re-establish him as a heavyweight title contender.

The Lyle fight was a proper restart; an opportunity to prove he was still the fighter who had stopped Frazier so decisively a few years earlier. It started ominously, though, with Lyle landing a big right hand flush towards the end of the first round, sending Foreman staggering across the ring.

Over the following four rounds, the two heavyweights unleashed fury on one another, trading blows and knockdowns in a brutal bout that seemed like it could go either way. But after a seismic fourth round during which both men hit the deck, it was Foreman who found it within himself to unleash a series of hard blows in the fifth round, bringing the Vegas crowd to their feet as Lyle staggered back into the ropes.

Amid cries of “Stop it! Stop it!” from concerned observers at ringside, the referee waved off the fight as an exhausted Lyle lay in a heap on the canvas. Foreman had answered many questions hanging over him after the Ali fight and made clear there was plenty more to come.

Michael Moorer vs George Foreman, Las Vegas, November 1994

Now 45 years old and a changed man from the moody, malevolent character he’d been earlier in his career, Foreman stepped into the ring to try to win back the heavyweight world title.

His life had taken quite a turn in 1977 when, just over a year after the war against Lyle, he’d been beaten by awkward American Jimmy Young in the sweltering heat of Puerto Rico. After all three judges awarded the bout to Young, Foreman headed into the changing room, where he quickly became unwell, suffering from exhaustion and heatstroke.

He later described having a “near-death experience” and it was one that left him in no doubt as to where his life was heading. He stopped boxing and became an ordained minister in the Church of the Lord Jesus Christ, dedicating his life to religion, his family and opening a youth centre in his name.

That lasted for 10 years before, in 1987, Foreman announced his comeback at the age of 38. Why? In his autobiography, he said he needed more money to fund his youth centre and also stated his ambition to fight Mike Tyson.

Many questioned the wisdom of returning, but Foreman wanted to show that age was no barrier and did just that, adding another 28 fights to his resume before meeting Michael Moorer to try to win a world title. Two of those were defeats, including one to Evander Holyfield that enhanced his credibility by dint of the strength and durability he showed against a man 14 years his junior.

It was another three years on from that fight that Foreman entered the ring against Moorer, who earlier in the year had beaten Holyfield to win the world title. Foreman had not fought for over a year after losing another bout, this time to Tommy Morrison in June 1993. It seemed the unlikeliest of outcomes that, at the age of 45, Foreman would be able to reach the top again against a man 19 years his junior.

Wearing the same red trunks as when he lost to Ali (perhaps with the waistband loosened a little) and with Dundee in his corner (the trainer spent many years in Ali’s corner), Foreman looked to be fulfilling expectations during the opening seven rounds when Moorer’s faster feet and hands allowed him to control the fight. But then the tide started to shift. Foreman found his timing and was starting to land some quick combinations that still carried plenty of the ‘Big George’ power.

Knowing he was behind on all three judges’ cards after the ninth round, Dundee told Foreman that he needed a knockout and that the time for it was now.

Late in the 10th round, Foreman found the shot, landing it flush on Moorer’s jaw and sending him down to the canvas, unable to recover before the referee’s count was over.

At 45 years and 360 days, Foreman became the oldest world champion in heavyweight history and the first man to regain a world boxing title 20 years after losing it.

In answer to later claims that the outcome was fixed, Foreman’s answer was simple: “Sure the fight was fixed. I fixed it with my right hand.”

(Top photo: Foreman against Frazier in 1973; by Bettmann via Getty Images)