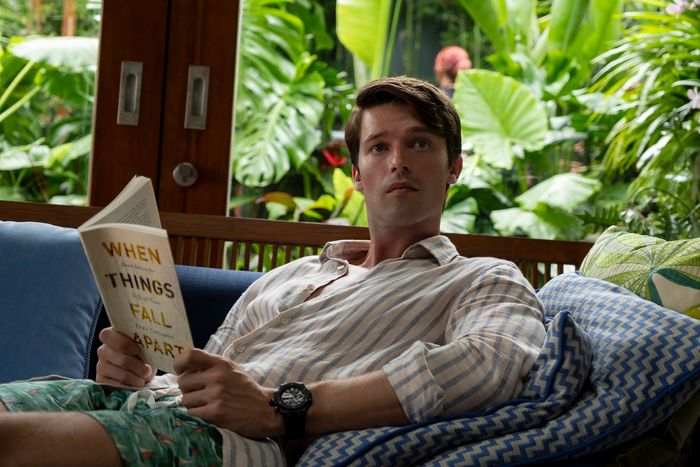

On The White Lotus, book titles are always worth keeping an eye on. Photo: Fabio Lovino/HBO

For more on The White Lotus, sign up for The White Lotus Club, our subscriber-exclusive newsletter obsessing over, dissecting, and debating everything about season three.

Spoilers ahead for The White Lotus season-three finale, “Amor Fati.”

Is a season of The White Lotus actually a season of The White Lotus if there are no moody montages of splashing sea water or significant book titles planted in poolside scenes? Don’t answer that: It’s a rhetorical, existential question. As noted in Kathryn VanArendonk’s review, this Thailand-set season is “most defined by all the ways the show keeps reaching back to what’s come before,” and several of Mike White’s go-to symbols, themes, and Easter eggs are on full display through these eight episodes. The dynamics within the upper crust-y Ratliff family nod to season one’s Mossbachers and season two’s DiGrassos, while themes of rebirth are rendered literal and monkey imagery comes to life. But how well did those recurring ideas communicate what this show is ultimately about? Let’s figure it out together over a possibly poisonous protein smoothie.

We got them in Hawaii. We got them in Sicily. And we got oh, so many of them in Thailand: repeated shots of waves lapping against the shore. Season three never quite delivered on its fascination with tsunamis—those dream sequences were more mood-setting—but it did give us one of the series’ more one-to-one equations of water and the afterlife. When Lochlan accidentally drinks a poisoned smoothie, he passes into another plane of existence, swimming through a deep ocean, looking up toward the bodies of four figures, who first appear to resemble the members of his family and then resemble Buddhist sages. He’s not the only White Lotus character to find a sort of peace in the waves. Remember that season one’s Quinn Mossbacher, a similarly wayward son, fled his family to go off rowing into the Pacific, an escape that’s presented as so idyllic it’s maybe too good to be true. Meanwhile, in season two, Tanya met her death more comedically, falling off her boat full of murderous gays, and there was a similar sense that in the ocean lies death, but maybe also, a kind of peace. That all ties into many of the recurring themes of the series: The idea that if you take the premise of travel, a desire to escape your life, to its logical extreme, you might end up somewhere near death. The abyss is a scary thing, and also, perhaps, freedom. —Jackson McHenry

Mike White has long been interested in Buddhism (as far as the mid-2000s, apparently), and so the fact he spent this season focused on “death, Eastern religion, and spirituality” didn’t entirely come as a surprise. In some senses, the thread has always been there. Recall, for example, that Sydney Sweeney wore a sweatshirt in the Hawaii vaycay emblazoned with “Bardo University” — the Bardo being a concept in Tibetan Buddhism referring to the intermediate space that comes after death but before rebirth. Isolated luxury resorts are, in a way, purgatorial spaces between pockets of life where you ostensibly go to be transformed. They are also hell, which is a fair way to describe the state of existence for many of the groups that make up a White Lotus season; how else would you refer to the marital agony Will Sharpe’s Ethan undergoes in the Sicilian outing? This time around, every visitor leaves the island in a new state of being: The Ratliffs are now poor, the girls-trip trio are rebonded, Belinda is now filthy rich, and Rick and Chelsea are in body bags. —Nick Quah

Each of The White Lotus’s three seasons has examined how money keeps the privileged in a bubble that protects them from the consequences of their actions. But what distinguishes the first two seasons from the third is the degree to which they humanize the financial underdogs and satirize those who have glided their way down a mountain of cash. The first season clearly asks us to empathize with people like Belinda, a hard worker who gets screwed over in a business deal by Tanya, or Rachel, a journalist who marries into a rich family without realizing the ramifications of that marriage. The second season outright makes the rich look like morons, killing off Tanya, who remains oblivious to the scam she’s fallen prey to until it’s way too late, and letting Sicilian sex workers successfully con the horny men of the DiGrasso family out of significant dollars.

While the third season makes familiar points about wealthy people being silly, self-involved ding-dongs, its takeaway message is much more muddled. The hard workers like season-one Belinda — Gaitok, for example — are often depicted as weak or comically inept. The only way for them to triumph is to hitch themselves to a problematic but lucrative situation, like Gaitok ultimately becoming security guard for Mrs. Hollinger or Belinda taking Greg/Gary’s $5 million despite her moral qualms. As much as this season of The White Lotus paints people like the Ratliffs in a bad light (a.k.a. the Duke University colors) it’s ultimately too timid to let us see what happens when their entire money-lined world blows up. —Jen Chaney

Nobody who checks into a White Lotus resort has ever had a notably good relationship with their father—the middle-aged men especially so. In season one, there was Steve Zahn’s Mark Mossbacher reckoning with the realization his dad was closeted and died of AIDS. (White’s own father, notably, was closeted for many years before coming out later in life.) In season two, Michael Imperioli’s Dominic Di Grasso tried to hold together some understanding of masculinity between his son and father. (White has said that plotline was inspired in part by a trip he took with his own father to rediscover their roots in Scandinavia.) In season three, we got a double serving of variations on the type: The family man in Jason Isaacs’ Timothy Ratliff, who has a whole lot of problems being a good patriarch and hiding the fact he’s lost all of the family’s money; and a man without a family in Walton Goggins’ Rick Hatchett, on a quest to avenge his father’s death.

How do those attempts to make peace with the concept of daddy go? Well, Timothy feels it’s going to be impossible for his family (except indecisive son Lochlan) to live without the wealth they’re accustomed to and serves them poisoned piña coladas, then abruptly changes his mind — though the remains end up going into Lochlan’s poisoned protein smoothie. The kid barely survives, though we don’t see Timothy face the blame for the poisoning, or the aftermath of his family discovering they’re broke and disgraced. As with Mark and Dominic, Timothy’s fatherhood is a thin facade, a performance of masculine strength that traps these men even as it also allows them to get away with various crimes. But with Goggins’s Rick, things reach the end of the line: In a fit of rage, Rick shoots the man he thought killed his father, only to discover that man was, in fact, his father. In the ensuing shootout, Rick is shot by Gaitok (another man who’s been told to be more manly) and so is his girlfriend Chelsea, the closest thing this season had to a bodhisattva. That’s a sort of dark mirror to some of the father issues we’ve seen in the first two seasons: While Mark and Dominic might’ve wished they could confront their fathers, face down their inheritance, and destroy the things they wished they didn’t carry around, Rick actually does, and he dies because of it. —JM

Season three continued White’s tendency to sprinkle book titles into various scenes like snarky literary Easter eggs. Belinda is at one point seen reading Surrounded by Narcissists, a non-fiction book by Thomas Erikson that could just as easily be the title of Belinda’s memoir. Michelle Monaghan’s self-absorbed actress thumbs through Barbra, a choice that announces her seriousness as a human being — it’s such a big book — and conveniently reminds anyone that she looks familiar because she, like Babs, is a Hollywood actress.

But in the finale, what’s most significant is that Saxon has finally started reading the meditation books Chelsea loaned him, a suggestion that he’s willing to admit his mind could stand to be more open. Meanwhile Lochlan, poor, dear, almost deceased Lochlan, opts for a book called A Wall of Ocean, which does not appear to be real, as far as I can tell. But it does serve as a bit of foreshadowing for his near-death experience, where he seems to be struggling under an ocean to reach the surface, a callback of sorts to Quinn’s desire to leave his family and return to the sea. Always pay attention to the books on this show! — JC

Sadly, a monkey did not turn out to be the mystery shooter. (Though that would’ve made for a more interesting ending.) Nevertheless, the animals’ recurring presence throughout the season visualizes the chattering, anxious feeling that governs the existential turmoil endured by many of the souls haunting the Thai White Lotus resort. This isn’t the first appearance of tormenting monkeys in the franchise, of course. Steve Zahn’s character in the Hawaii jaunt equates his animal need to jack off to the primate: “You’re a monkey. Like possessed. You’d do anything to get your rocks off. And then, later, you regret it… There’s the man, and there’s the monkey. And somehow, you gotta be man enough to face down the monkey.” Monkeys have appeared in the opening-credits mural art for all three seasons, though in Sicily, it evoked more of a sense of debauchery than in Thailand, where the focus is tethered to the metaphor of the “monkey mind.” This is first verbalized by Amrita, the resort’s wellness guide, during her session with Rick, referring to the state of restlessness that distracts people from meditation, and thus, a stillness of interiority that may yield enlightenment. It’s grim symmetry that the explosive events of the finale is precipitated by Rick seeking out Amrita in a desperate attempt to be talked (or meditated) down from the edge of taking the rash action that would end in his and Chelsea’s demise. I suppose you can say that Amrita’s professional commitment to keeping her schedule was the reason the shootout ultimately happened. Alas, if only she gave him five minutes! A monkey might not have been the one to pull the trigger, but the monkey mind totally did. —NQ