This article contains spoilers for Happy Face.

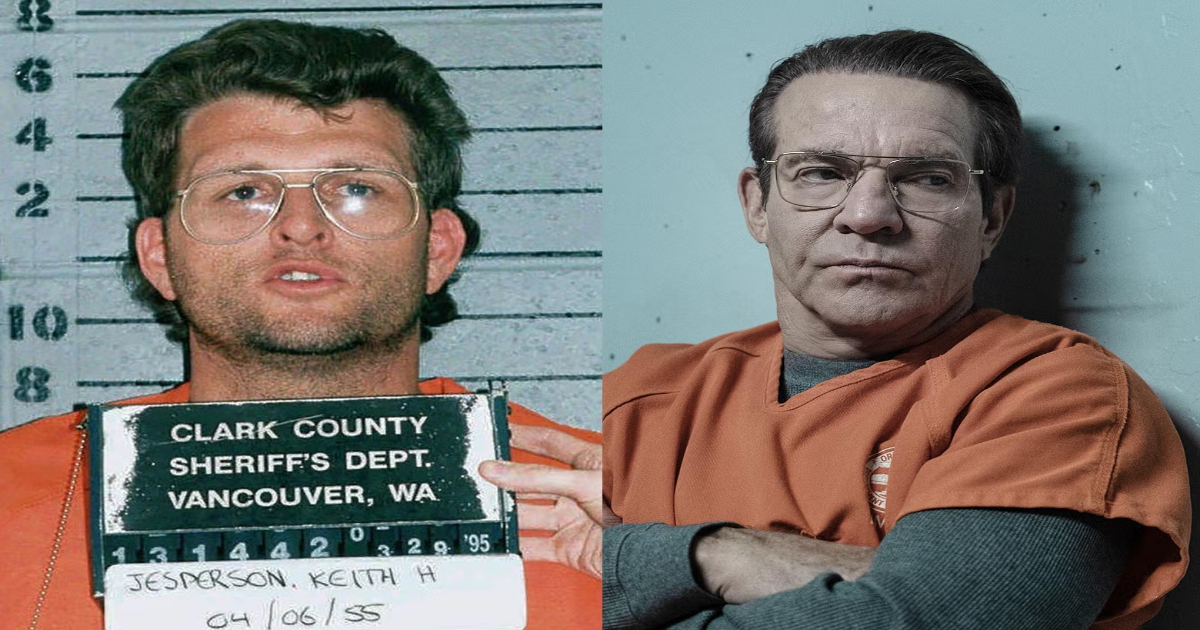

Paramount+’s new series Happy Face seeks to be both a true-crime drama and a critique of the genre—having its cake and eating it too, dramatically speaking. The series is based on a memoir and spinoff podcast by Melissa G. Moore, and explores her coming to terms with learning Keith Jesperson, the father she loved and adored as a child, led a double life as the notorious “Happy Face” serial killer (so dubbed due to his fondness for leaving confessions signed with a happy face at the scene of his crimes).

However, the focus of the series is not really on Jesperson’s crimes and bringing him to justice (he’s already serving a life sentence when the story starts), but rather on the rippling impact of the murders on members of the victims’ wider families, including young people who were not yet born when the crimes took place. This bit of time-bending allows the story room to explore Moore’s own complex family dynamics.

At the same time, the series looks at how the expanding (and lucrative) true-crime media ecology has turned psychopaths into objects of fascination and, if not actual role models, at least cult figures … even as Happy Face itself contributes to this phenomenon. (It’s worth noting that it could be argued this has been happening since the days of Jack the Ripper.) In any case, here we look at this account of a daughter coming to terms with loving an evil father to determine where it’s myth-building and where it’s myth-busting.

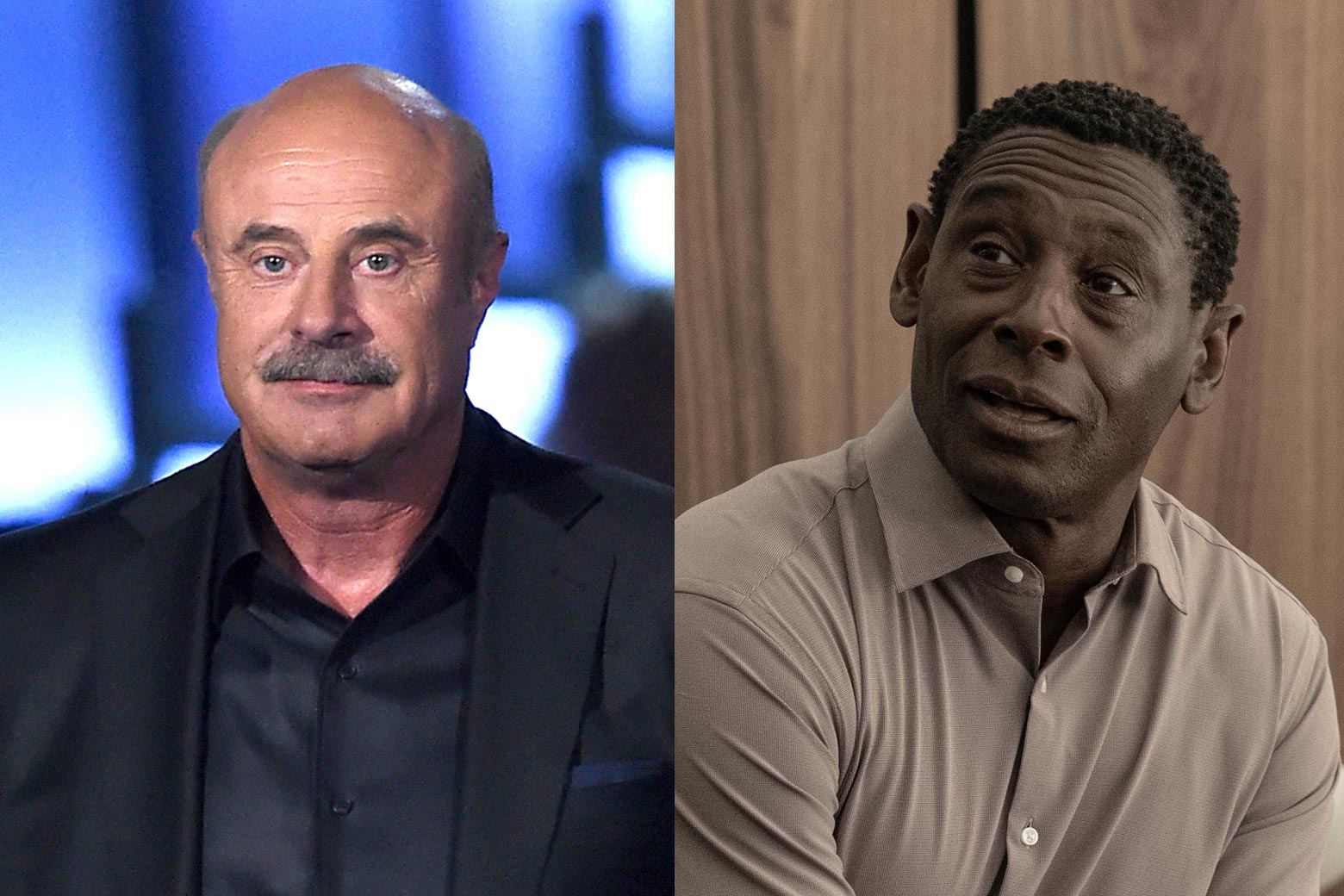

In the series, Melissa Reed (Annaleigh Ashford) is working as a makeup artist for the Dr. Greg Show, a sort of Dr. Phil/Dr. Oz–like talk show where the charismatic Dr. Greg (David Harewood) provides informal counseling, in front of a live audience, to people dealing with some kind of psychological trauma, including those who have lost a loved one to violence. One day, Melissa’s estranged father, the convicted serial killer Keith Jesperson (Dennis Quaid)—who is serving time for eight femicides—phones the show wanting to confess to one more murder, but says he will only confide the details to Melissa.

Melissa wants no contact with her father, but Dr. Greg is naturally thrilled to have an inside line to this juicy story and gets his ambitious producer, Ivy, to convince Melissa to cooperate by pointing out that Keith’s revelations might help another family find closure, which results in the two going to visit Keith in an Oregon penitentiary. Although Melissa is determined not to let Keith back into her life, he lures her in by telling her that his ninth victim was a bartender he picked up when he came across her hitchhiking in Texas. When Melissa learns that the bartender’s boyfriend is on death row for the murder and awaiting imminent execution, she and Ivy feel obligated to get the case reopened. They start interviewing people connected to the case, and Melissa proves to be a natural journalist, knowing when to confront and when to back off and possessing a remarkable ability to get people to open up to her.

The real Melissa G. Moore never worked for a Dr. Phil–like show in any capacity or, as far as is known, worked in the media at all prior to 2008. Nor has there ever been a nationally syndicated talk show hosted by a doctor emanating from the Pacific Northwest. Moore did get to know psychologist Phil “Dr. Phil” McGraw in June 2008 when she attended a “Get Real Retreat,” an intense three-day therapy session hosted by McGraw. McGraw had suggested Moore attend after she wrote to him in desperation asking if she should continue to have a relationship with her father. McGraw advised her to have nothing more to do with Keith (unlike the series’ Dr. Greg, who, again, suggests she resume contact for the sake of the show).

For 15 years, the secret of Moore’s past had been known only to her husband and her best friend. However, she later said the Get Real Retreat helped her to stop feeling shame and open up about her situation, recalling, “I went on the retreat to find out if I should have a relationship with my father. I know that sounds absurd now, but I was receiving letters and I felt so guilty as a daughter. He was my father and didn’t have a conscience; he didn’t show remorse for the victims. I took it upon myself to feel that burden, that guilt, for him, and I didn’t realize I did that.”

In the series, after Melissa’s appearance on his show generates a huge public response, Dr. Greg invites her and her husband, Ben (James Wolk), to dinner with him and his wife. Expecting a casual dinner party, Melissa arrives at Dr. Greg’s impressive home to find an array of terrifyingly well-groomed people who turn out to be Dr. Greg’s television agent, his literary agent, a film producer, his social media agent, and all the other enablers of a modern media career. They all seem to want to get to know her and are hungry for more salacious details of her father’s crimes and what it was like to live with a serial killer. Pleading a headache, Melissa leaves the dinner early, although Dr. Greg reminds her: “This is your moment,” and says that she should seize the opportunity. Melissa insists she has no interest in a big media career and just wants to get the man wrongly convicted for what she thinks was her father’s crime exonerated and then go back to normal life.

In reality, after a November 2008 appearance on the Dr. Phil show based on her therapy at the Get Real Retreat, Melissa was featured on The Oprah Winfrey Show and a 20/20 special on ABC. She appeared in an episode of the true-crime television series Evil Lives Here and was a correspondent for a program called Crime Watch Daily. Far from dismissing the suggestion that she write a book, as she does in the series, she did exactly that at Dr. Phil’s urging and in 2009 published Shattered Silence: The Untold Story of a Serial Killer’s Daughter, which led to the Oprah interview that really put her on the media map. She then followed this up with two more books, both around the theme of recovering from a bad upbringing and childhood trauma. She also produced two true-crime podcast series—Happy Face and Life After Happy Face—and helped create the A&E series Monster in My Family, which explores how being connected to notorious criminals has affected the lives of individual people.

According to Moore, she was motivated not by finding fame but by helping others, telling the BBC in 2014, “After I appeared on the Oprah Winfrey show in 2009, I received hundreds of emails from family members of other serial killers thanking me for telling my story, and asking for help and advice.” She also said she has created a network of more than 300 people who are related to killers, to whom she speaks both on the phone and in person.

In the show, Melissa and Ivy discover that the ninth victim Keith told them he killed was not only a bartender, but a talented singer-songwriter named Heather. They further discover (as mentioned above) that Heather’s then-boyfriend, Elijah, another musician, was convicted of her murder and has been on death row for decades, although he has always maintained his innocence. They team up with Elijah’s sister, who has advocated tirelessly for her brother over many years. After many twists and turns, including uncovering a corrupt district attorney who arranged for DNA evidence to disappear and finding that Keith arranged for evidence to be fabricated to connect him to the crime, they prove Elijah’s innocence. Then, displaying nearly Sherlockian detecting skills, Melissa deduces who the real killer is and manages to get a confession from him.

In reality, there was no Heather and thus no Elijah. Most of Jesperson’s victims were sex workers and transients whom he picked up when they were hitchhiking, not aspiring musicians. As for the wrong person being locked up, the show’s creators appear to have done some conflating with the case of Jesperson’s first victim, a young woman named Taunja Bennett, whom he raped and killed in 1990 in Portland, Oregon. At first, he got away with the murder because a local woman named Laverne Pavlinac told police she had helped her partner John Sosnovske rape and kill Bennett—she later confessed that she had invented the confession to get revenge against Sosnovske for domestic abuse. The lead detective on the case told the Netflix true-crime program Catching Killers that he genuinely believed the “grandmotherly” (she was 57) Pavlinac’s story. Both Pavlinac and Sosnovske were found guilty and sentenced to life in prison.

Furious that someone else had claimed “credit” for his work, Jesperson (a long-distance trucker) left “confessions” for the authorities scrawled on the bathroom walls of truck stops and wrote letters to various media outlets, signing each one with the smiley face that gave him his tabloid name. All were ignored, but one six-page missive, in which he confessed to subsequent murders, saying, “She was my first, and I thought I would not do it again. But I was wrong,” went to the Oregonian. There, investigative journalist Phil Stanford did take him seriously and wrote several columns alleging that Pavlinac and Sosnovske had been wrongly convicted.

Then, in March 1994, Jesperson was arrested for the murder of another victim and confessed to seven other murders, including Bennett’s. After he provided details of her murder that only the killer could have known, even the state prosecutors were asking for the couple, who by now had served five years, to be freed. Meanwhile, Taunja Bennett’s sister became an outspoken critic of how the case had been handled as it resulted in the real murderer escaping justice.

At Dr. Greg’s dinner party, Melissa recounts a chilling story of caring for some kittens in the basement as a child until her father found them and hung them by their tails from a clothesline as an anguished Melissa watched, her father smiling as the kittens writhed and scratched themselves to death.

This actually happened. As Moore told the BBC, “When I was 5, I found these beautiful little kittens in the cellar of our farmhouse and I took them outside to play with. When my dad saw what I had in my hands he took them, casually hung them up on the clothesline, and began to torment them. I remembered his enjoyment as I screamed and pleaded with him to take them down. Later on, I found their little bodies in the back garden.” Furthermore, in common with many serial killers, Jesperson had a history of torturing animals dating back to childhood.

The series shows Keith making contact with his granddaughter Hazel, whom Melissa has tried to keep unaware of his existence, by sending her a hand-drawn birthday card. As the two clandestinely start talking by phone, he sends her several drawings. Hazel, something of an outcast, is delighted to find that rather than attacking her for having a serial killer as a grandfather, the class mean girls think it’s cool, and the cute boy she has a crush on offers to let her use his internet payment account if she wants to sell the drawings online. It turns out there is a viable market for Keith’s artwork, not only from internet buyers but also from a museum devoted to serial killers.

Although it is not known if Moore’s daughter (who is not called Hazel) ever contacted her grandfather, there is indeed a market for Jesperson’s drawings, with works selling for up to $600. There are also no fewer than three museums in the U.S. exhibiting memorabilia connected to serial killers—one with locations in Hollywood and New Orleans, one in North Carolina, and one in Tennessee.

Get the best of movies, TV, books, music, and more.