The two armies, while regularly shelling one another, established hotlines. Generals would invite one another across the frontline to go duck shooting.

When the Telegraph visited the contact line in 2019, a Pakistani officer explained that we were in view of Indian snipers who had only recently opened fire but predicted with confidence there would be no fighting that day.

“If you look over there, you will see they have visitors too today.” Sure enough, on the other side of no-man’s land, a small group of what were presumably Indian journalists could be seen peering curiously in our direction.

This level of coordination should not be romanticised. The grim logic of nuclear deterrence – India got the bomb in 1974, Pakistan in 1998 – has been at least as important as the water treaty in dampening the desire for full scale confrontation.

But on the whole, the conflict has been relatively well regulated. The fear now is that all those safeguards could come tumbling down.

“They’ve been at it for such a long time, and there are certain rules of engagement. Now those rules of engagement are being questioned,” says Bajpaee.

“Back in 1999 both countries went to war in Kashmir, but the Indian military response was so restrained they refused to send fighter aircraft across the border into Pakistan-administered Kashmir. That has all changed under the Modi government. In 2016, they carried out strikes in Pakistan-administered Kashmir. And in 2019 they conducted air strikes in Pakistan proper.”

Still, he says, there are some limits notionally in place. Water is one. “These are lines that, essentially, can’t be crossed.”

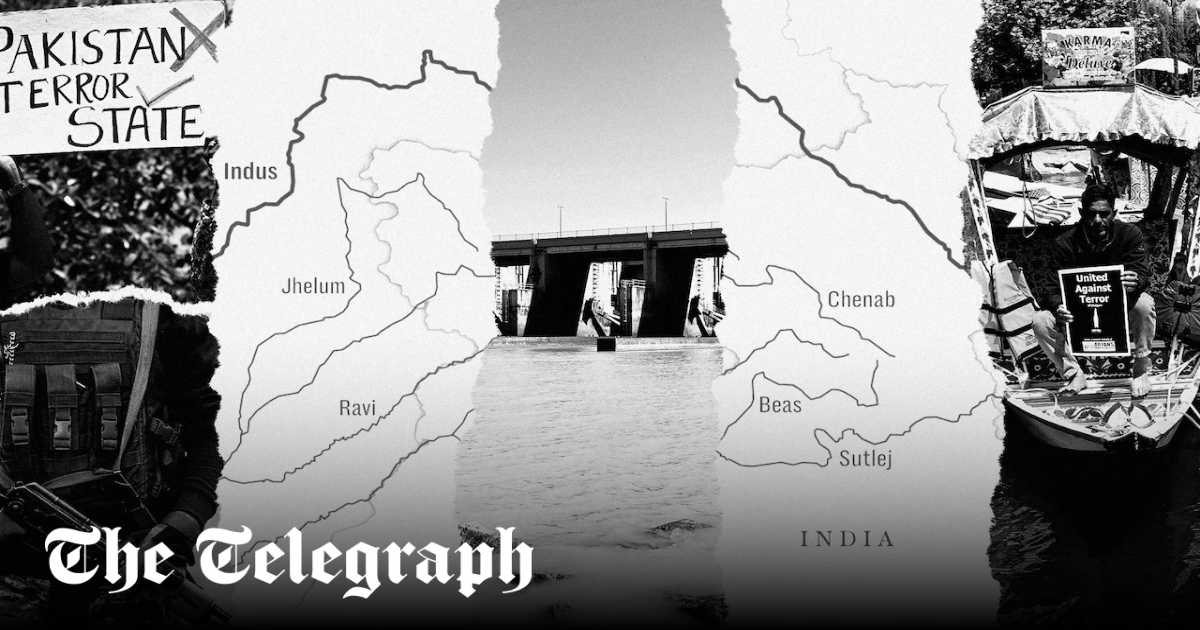

Water wars

When it comes to using water as a weapon of war, says Michel, “the Indus has long been on the radar.” But it is far from alone. “The usage of water management as a tool of geopolitical leverage has been an emerging challenge.”

The most infamous water conflict is in the Jordan river valley, where so much water has been syphoned off that the river is little more than a trickle by the time it reaches the Dead Sea.

The Nile is another example of upstream dependency, with Sudan and especially Egypt almost entirely dependent on rains that fall on the Ethiopian highlands.

In the Tigris and Euphrates system, Syria and Iraq have both accused Turkey of using its control of the headwaters to exert political pressure. At one point Turkey and Syria signed an explicit conflict-related water deal – Turkey promised to release more water to Syria if former leader Bashar al-Assad ceased backing the PKK, a Kurdish insurgent group.

In the Mekong river system, meanwhile, China has been building hydroelectric infrastructure both on its own portion and in that of neighbours like Laos and Myanmar – to the alarm of Vietnam, Cambodia, and Thailand.

India, at large, is itself a downstream nation. The Brahmaputra river, in the country’s east, rises in China and is vulnerable to an enormous hydroelectric project planned by Beijing.