Sitting in his hotel near the banks of the Lidder river, P S Bali, a manager at a hotel in Pahalgam, points to a park in the distance. “On Monday, it was like a festival out here,” he tells The Indian Express. “There were hundreds of tourists, singing, whistling and screaming in joy. Today is desolate. It’s heartbreaking. All the tourists have left Pahalgam. We hope this is not permanent but we fear it will have a huge impact. It seems the Pahalgam story has ended for this season.”

Bali echoes the general sentiment – and heartbreak – of Pahalgam in Anantnag district, one of Kashmir’s most popular tourist destinations and health resorts. On Tuesday, 26 civilians – mostly tourists about also a local pony wallah – were shot dead by some unidentified attackers at Pahalgam’s Baisaran meadow: one of the worst terror attacks on civilians Kashmir has seen in recent times. The attack, which was widely condemned across the Valley and saw shutdowns being observed in Jammu as well as Kashmir, has sparked fears about the ripple effect on the union territory’s mainstay – tourism, which had just begun to emerge from the shadows cast by the pandemic.

Story continues below this ad

Read | ‘It seemed like an eternity’: What happened when terror struck Pahalgam’s Baisaran valley

Instead, all roads to the picturesque health resort have been sealed and a search operation is currently ongoing, with security forces scouring Pahalgam’s dense forests around it to trace the attackers.

People hold a candlelight vigil to pay tribute to the victims of the Pahalgam terror attack, outside Jamia Masjid Nowhatta in downtown Srinagar. (PTI Photo)All the bookings for hotels in Pahalgam for the next two-three days have been cancelled, a tourism official tells The Indian Express. “The impact is visible beyond Pahalgam as well. There are reports that tourists are cancelling their Kashmir visit in large numbers”.

People hold a candlelight vigil to pay tribute to the victims of the Pahalgam terror attack, outside Jamia Masjid Nowhatta in downtown Srinagar. (PTI Photo)All the bookings for hotels in Pahalgam for the next two-three days have been cancelled, a tourism official tells The Indian Express. “The impact is visible beyond Pahalgam as well. There are reports that tourists are cancelling their Kashmir visit in large numbers”.

Indeed, restaurants around Pahalgam bear witness to this. “Our faces tell our story,” Umar Majeed, a 25-year-old owner of a restaurant in Yanner, where restaurants are closed in protest, says. “There are tears in our eyes but we can’t even shed them”.

Sabzar Ahmad Mir, another restaurant owner at Yanner, says that it wasn’t until later that they knew what had happened.

“We were busy serving the tourists,” he says. “Suddenly, we saw a huge crowd of tourists moving towards us. They were in panic. In barely an hour, the whole area had emptied.”

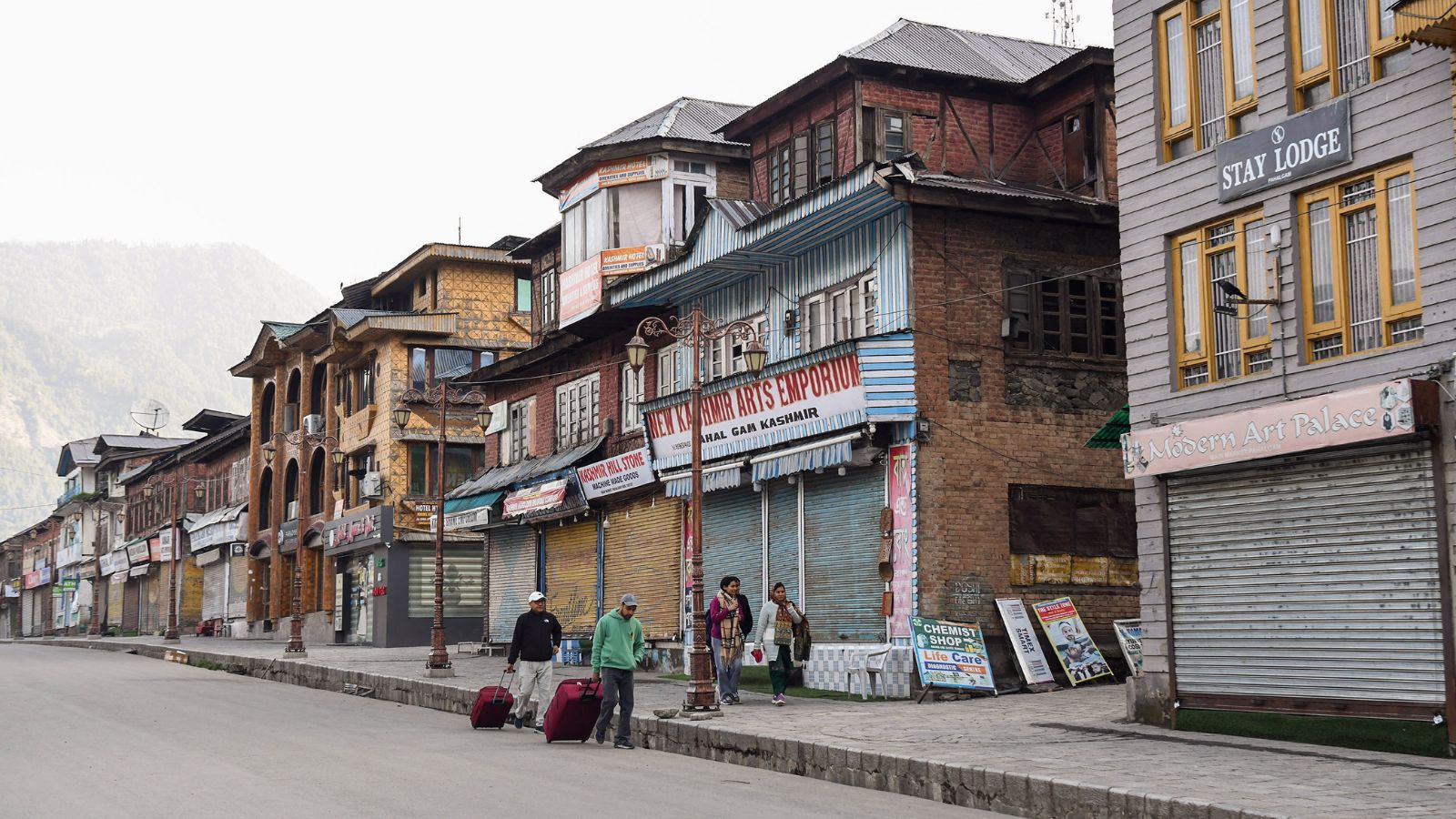

At the usually buzzing Pahalgam market, now shut in protest, there’s a ringing silence.

“What can we say?” one man sitting outside his closed fast-food vending shop, finally ventures. “It was just the beginning of the season and it’s now finished. I had brought stocks worth seven lakh rupees hoping for a booming season this year. All that has been lost.”