This post contains spoilers for Season 2, Episode 2 of The Last of Us.

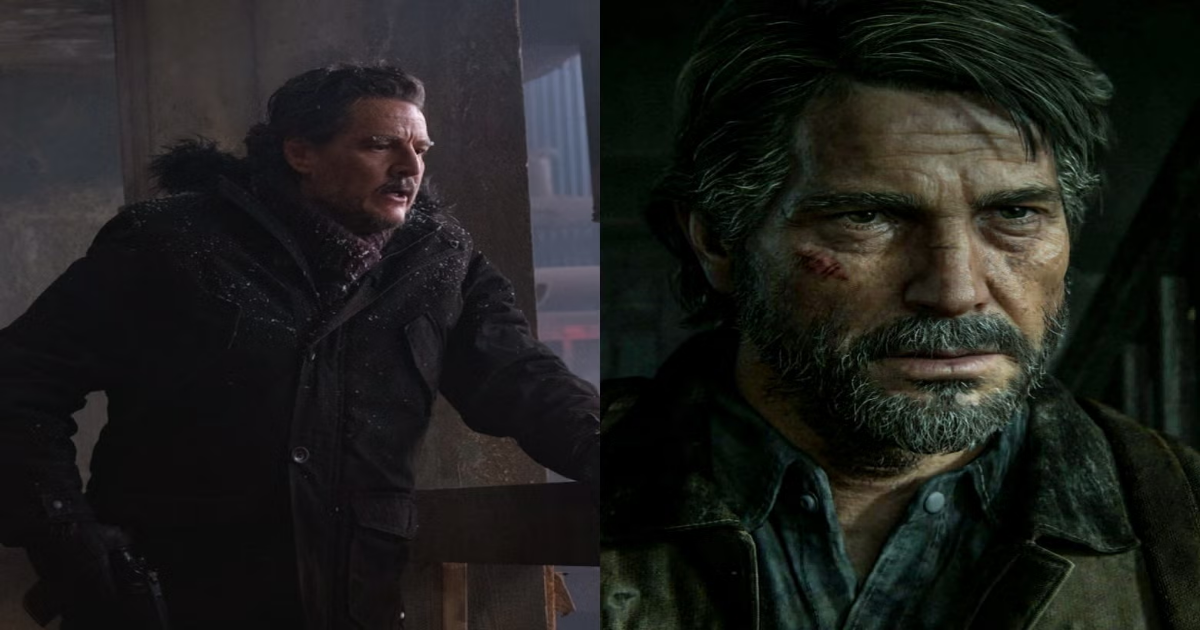

Folks, that’s a series wrap for Pedro Pascal. Joel, one of the two protagonists of HBO’s adaptation of the hit video game The Last of Us, is dead. He was murdered by a band of ex-Fireflies in the second episode of Season 2, which aired this Sunday. The Fireflies, you might remember, are the paramilitary organization that Joel destroyed at the end of the first season. He followed through with that assault because he couldn’t stomach the idea of Ellie, the girl who has become like a daughter to him, being sacrificed in search of a cure for the rampaging fungal virus that has brought about a dire apocalypse. And in that sense, you can’t really say Joel didn’t have it coming. Still, it’s not easy watching his gruesome death, both in the game and now on the TV screen. But that marquee moment was inevitable: Joel gets beaten into a bloodied half-consciousness with a golf club before matters finally end—in front of a restrained Ellie, no less—with a steel stake through the ear. That’s it. There is no miracle cure coming. It wasn’t all just a dream. Pascal will be on flashback duty from here on out.

Those of us who played the games knew to dread this scene, although it wasn’t clear when—or even if—HBO would hold true to the source material and kill off one of its two leads. Did the sequence feel, maybe, a tad overcooked? Perhaps a bit too self-aware in its bloodletting? As if it set out to validate its own literary auspices? I wouldn’t fault you for feeling that way, because—in many ways—a commitment to careening dramatic swings has been central to The Last Of Us mythology for quite some time. Sometimes the subversion pays off beautifully. Other times? Well, your mileage may vary.

In the video game, the violence is cruel and unusual. Joel’s death occurs in the prologue—the prologue!—and it’s cued up to be the animating agent for the rest of the narrative. Joel and his brother Tommy rescue a hardened survivor, who we learn is named Abby, from a rampaging swarm of zombies. This is terrible luck, because little does Joel know, the only reason Abby is in Wyoming is to hunt him down. So, Abby lures Joel back to her hideout, brimming with her paramilitary goons, to spring her trap. Tommy is incapacitated, and Joel is beaten with a golf club, tortured with icy sadism. (“You don’t get to rush this,” says Abby, when she has him in her grasp.) Ellie is actively searching for Joel, who never made it back from patrol. She stumbles upon Abby’s hideout, but is discovered, knocked down, and forced to watch the last moments of Joel’s life. Her surrogate father is crumpled on the ground, nonverbal, when Abby delivers the final blow across his forehead with that golf club. One member of her party spits on Joel’s desecrated body and wishes him a speedy trip to hell.

So why does Abby want him dead? It’s simple: Joel murdered her father, who was one of the doctors operating on Ellie at the end of the first game. This is one of the key ways the TV show deviates from the video game. On the PlayStation, the sorrow at the core of Abby’s revenge is meted out carefully over hours of flashbacks—slowly exposing the context of Joel’s undoing, and all the people he had wronged. On HBO, however, all of the exposition is provided up front. Rather than Tommy (Gabriel Luna), Joel is traveling with Dina (Ellie’s brand-new girlfriend, played by Isabela Merced) when they save Abby (Kaitlyn Dever) from a horde of infected. She takes them back to the ski lodge, where the ambush occurs. Dina is subdued with an anesthetic while Abby unleashes a Bond-villain monologue identifying the precise terms of her vengeance. (Joel killed her father, upended the Fireflies, and severed one of the Earth’s only hopes for a cure, etc.) Her fellow avengers voice halting protests in the background. They want to see Joel murdered, but not like this—a stark contrast from blunted hatefulness in the mother text. Eventually, with Ellie (Bella Ramsey) serving as a witness, Abby ends Joel’s life with a stake through the ear, using the broken-off end of the golf club.

All in all, it’s a pretty faithful rendition, but it also accentuates my hang-up with The Last of Us as the show marches onward into the reedy territory of the game’s one and only sequel. When I consider how delicately the first game, and first season, unveiled its knotty morality—how it flat-out refused to provide easy answers for its difficult questions—I can’t help but feel underserved by a continuation of a story that takes great pains to remind me, at every turn, of a flat bromide we already understand implicitly: Revenge is never as satisfying as it manifests to be in our fantasies. It’s a make-or-break moment for one of HBO’s biggest hits. Will audiences decide that the show has earned Joel’s death? Or will they, like so many gamers, come to find that something is missing?

To really understand the earth-shattering impact of The Last of Us, and why the series would eventually become emboldened enough to ice its most popular character, you must also understand the contours of the video game industry. In the years before the game’s release in 2013, Naughty Dog—the studio responsible for this grimdark fungal apocalypse—had issued a trilogy of Indiana Jones–aping romps under the Uncharted name. The formula was pure camp: Uncharted starred a good-looking treasure hunter named Nathan Drake, and the rest of the cast was filled out by his inner circle of tropey sidekicks, including a femme fatale, a cigar-chomping pilot, and, eventually, a long-lost ne’er-do-well brother. It worked—those games are good—but they were also confined to their shopworn narrative aspirations. Naughty Dog set out to ape a Marvel-fied version of Hollywood, replete with writerly quips, pulp-adventure intrigue, and swashbuckling violence. The developer succeeded, but Uncharted would never be mistaken as, well, art. (Naturally, when an Uncharted movie hit theaters in 2022, it was unable to overcome the derivativeness at its heart, and was roundly panned.)

The Last of Us, then, was a genuine evolution for Naughty Dog. The game was built on a steadfast belief that with enough care and attention, a PlayStation can be capable of matching the hallowed echelons of the Hollywood canon. So the studio put us in control of Joel, a violent man with a brutal past, whose arc in the first game concludes in a hospital where he makes a horrifically selfish decision. This ending, the same one that was immortalized in the Season 1 finale of the TV adaptation, is, quite literally, my favorite scene in video game history. The script was indelible, especially Ellie’s ambiguous half-acceptance of the lie that both she and Joel have decided to live—that the operation to harvest her immunity didn’t work, and therefore neither of them are personally complicit in the ugliness of this world. But on a more meta level, the thoughtfulness of this ending signaled that something had shifted in the culture. This was a video game delivering a gut-punch, feel-bad, Godfather-esque coda. The technicolor pleasures of Uncharted had been tossed into a ditch. Naughty Dog wanted to make the game industry’s first big-screen tragedy—on the mythic scale of John Ford—and actually pulled it off.

That’s why, seven years later, I was surprised that Naughty Dog was returning to the well with a sequel game. Why bulldoze over the haunting puzzle of that perfect final scene with corroding certitude? I never really wanted to know what happened to Ellie and Joel after that. But the studio clearly had a vision, and that required the merciless destruction of the leading man in The Last of Us Part II, which was released in 2020. This, too, was a watershed moment for Naughty Dog, but only in the sense that it plunged the company into controversy. A huge number of Gamergate-aligned chuds leveraged the sequel into culture-war grievance for predictably stupid reasons. (You no longer played the game as a white man. And also, later on in the narrative, a trans character becomes central to the plot.) Really though, Joel’s death was evidence that Naughty Dog had achieved the creative cachet necessary to wield total control over its intellectual property—almost like the studio wanted to levitate above the commercial bindings of the games industry. Nintendo can’t kill Mario, Microsoft can’t kill Master Chief, but Naughty Dog is more than willing to assassinate Joel, so long as it helps make a point.

And it was certainly brave, but even good-faith critics took issue with the overwhelming darkness of the twist, especially given how it’s set up as a pretense for—without a doubt—the most ruthless revenge saga ever rendered on a graphics card. Without delving into spoilers for the rest of the second season on HBO, one of the main criticisms of The Last of Us Part II was that its thematic texture lacked sophistication. The threads it spins all inevitably arrive at the core conceits of the series—that violence begets violence, no matter how much the target deserves it—and to some, that’s not a profound enough motif to merit all of the crimes against humanity that Ellie has now set out to accomplish. Her retribution will be wide, uncompromising, and absolutely suffused with gore, but it all belies the thinness of the fiction.

There are, of course, more episodes coming, but it is fair to say that our story will only grow darker from here. Ellie must achieve her vengeance, and we, the captive audience, must come along for the ride. Perhaps the TV show will manage to refine what was achieved in the video game, finding more intricate complexities in the muck of all this violence. If not, then I do wonder if newly born The Last of Us fans will eventually come around to my thinking. Maybe this story was better off leaving Joel and Ellie on that grassy knoll, where all possibilities—good and bad—stretched out into the horizon. You know what’s the real skill of the artist? Knowing when you’ve hit one out of the park.

Get the best of movies, TV, books, music, and more.